Ferreting out the Fakes

They're at it again—or, we should say, still.

You can actually type into your search engine "fake jewelry near me" and get pages of shopping outlets. And these are sources that admit their wares are only mimicking the real thing.

You can actually type into your search engine "fake jewelry near me" and get pages of shopping outlets. And these are sources that admit their wares are only mimicking the real thing.

For jewelry buyers and jewelry insurers, there are many kinds of "fakes," many substitutions, deceptions, and omissions to guard against. Some are more obvious than others.

Counterfeit brands

Law enforcement frequently finds truckloads of counterfeit brand-name jewelry (and other luxury items) at customs checkpoints, as many brand knockoffs are produced abroad. Customs officials reported in 2020 the agency seized more than 26,000 shipments containing counterfeit goods, worth $1.3 billion if they had been genuine.

Other counterfeit hauls are discovered quite by accident. Three individuals were arrested in New York when police stumbled upon 5,000 fake Rolex watches during a raid of a home in connection with a drug operation. Prosecutors stated that the defendants used the sale of counterfeit items to launder drug money.

When suppliers or sellers of knockoffs are caught in the act, they may get some press attention because of the famous names and big money involved. Sometimes a lawsuit follows. In 2019, luxury jeweler David Yurman was awarded $1.5 million in a suit over the sale of knockoffs of his jewelry.

If the shipments are not caught and wares get through, they'll probably find their way to website retailers and auction sites. Luxury brands constantly monitor the internet for sites selling cheap merchandise with their respected name on it. Several years ago, Tiffany & Co. found that 73 percent of the sales on eBay involved frauds.

Rolex watches are a prime target for jewelry counterfeiters. It's estimated that 10 times more fake Rolexes than genuine ones are put into circulation each year. These are the odds you face when insuring a Rolex. See fake Rolexes for a more detailed exploration of the problem.

Some websites openly advertise that they are selling knockoffs, leaving no doubt that the customer is buying only for the name. Other outlets just charge low—or even ridiculously low—prices for merchandise carrying a famous name.

The jewelry customers may know it's a knockoff, or they may choose to just believe they got a really, really good bargain. In either case, they may represent it to the insurer as an authentic and high-value brand-name piece.

Misidentified gems

Natural Citrine

Natural CitrineSometimes sellers will pass off low-priced gems as more valuable gems of similar color, assuming the customer will not know the difference. Natural citrine, for example, is very rare, but almost all material sold with that name is actually heat-treated amethyst. Or pinkish sapphire may be sold as ruby to fetch the higher price that ruby commands.

Diamond has many imitators—cubic zirconium, moissanite, glass. In one fraud, a stone made of CZ is coated with a thin layer of diamond, so it looks like diamond and even tests as diamond because its surface is diamond.

One seller skipped the identity step altogether. A full-page magazine ad pictured what was described as a 1-carat solitaire ring at a remarkable price. It looked like diamond—but nowhere did the ad say it was diamond. It wasn't.

Non-Disclosure

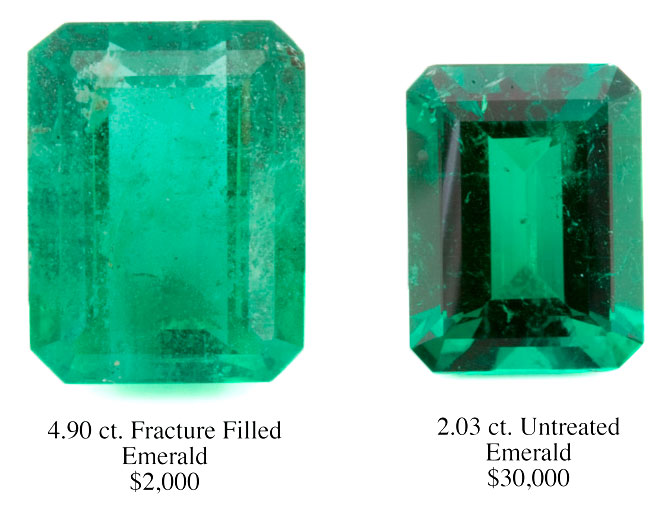

Lack of disclosure is a subtler form of fakery. In this fraud the gemstone is accurately identified but important information is left off. For instance, a seller may neglect to reveal that the gem is fracture-filled.

Such treated gems will look better, but they still contain fractures that lower their value compared to untreated gems and that leave the stone more vulnerable to damage.

Lack of such information often occurs on website auctions, in TV sales, at flea markets, and at shops in tourist areas. The customers may not understand how jewelry is valued or know what questions to ask. They may just be impressed by the sales pitch and moved by the emotion of the moment. The jewelry they buy is often overpriced and of far lower quality than they were led to believe by the salesperson or by the appraisal they received. [A future JII will alert insurers to fakery issues involving jewelry appraisals and lab reports.]

Lab-grown diamonds are a special case for potential fraud. A lab-made diamond is real diamond (not fake), but in the current market it is worth less than mined diamond of similar size and quality. If the seller neglects to reveal that a diamond is lab-made, the customer is misled about the value of their purchase. Both the customer and the insurer should know whether the gem is mined or lab-grown.

Several parcels of diamonds sent to GIA Laboratories for grading have had lab-made stones mixed in with mined stones, presumably to see whether GIA could detect the difference. GIA has some of the best equipment and expertise for recognizing lab-made diamond. But it is unknown how many lab-made stones slip into the market and are sold, priced, and insured as mined diamonds.

Avoid moral hazard!

The purpose of any fakery—whether it's a brand knockoff, inadequate information, or deliberate fraud—is to supply the appearance of quality but at a much lower cost. That apparent quality allows the seller to get away with charging more than the item is worth.

And here, caveat insurer!

Insuring fake jewelry for the price of the real thing creates serious moral hazard. A clever fraudster could make a killing with a fictitious loss claim. Even a naive consumer, who discovered after their purchase that the jewelry was worth much less than they paid (and insured it for!), might be tempted to recover their outlay through an insurance claim.

The insurer's responsibility is to make the insured whole, replacing with like kind and quality. You don't want to be replacing a cheap knockoff with a pricey brand name piece. Since insurance professionals are not jewelry experts, they must rely on evidence of the jewelry's quality and value.

So, best practice:

- Sales receipt

Rather than relying simply on the possibly inflated valuation, ask for the sales receipt, as the price paid is more likely to represent current market value.

- Appraisal from a trained and reliable appraiser

We recommend an appraisal that includes the JISO 78/79 appraisal form (a rarity these days!) and is written by a qualified gemologist (GG, FGA+, or equivalent), preferably one who has additional insurance appraisal training.

- Lab report from a reputable grading lab

We recommend these highly respected labs, and you can use these links to verify reports you receive:

Gemological Institute of America GIA Report Check

American Gem Society Lab AGS Report Verification

Gem Certification and Assurance Lab GCAL Certificate Search

FOR AGENTS & UNDERWRITERS

Clarity treatments such as fracture filling are done to conceal flaws in the gem. The fractures may not be visible to the unaided eye, but a trained gemologist with basic gem lab equipment can easily see them.

Clarity treatments such as fracture filling are done to conceal flaws in the gem. The fractures may not be visible to the unaided eye, but a trained gemologist with basic gem lab equipment can easily see them.

A gem with fractures, whether filled or not, is weaker and more susceptible to damage.

There is always the danger that gem treatments will not be disclosed—by the supplier, the dealer, the jewelry manufacturer, the retailer, or the consumer—either out of ignorance or as deliberate fraud. The insurer is at the end of this chain and could wind up grossly overpaying a claim.

FOR ADJUSTERS

Be wary of fraud. The insured may know the jewelry is fake and try to cash in through an insurance claim. Use every means possible to be sure a high-value item is genuine.

With diamonds, the price difference between mined and lab-grown is far greater than with most other stones. Mistaking a lab-grown diamond for a mined one could mean an overpayment of tens of thousands of dollars.

Carefully examine all documents on file. A treatment like fracture-filling may not be disclosed on the appraisal but may be mentioned in boilerplate text in brochures or other materials supplied by the seller.

The sales receipt is important. If there is a huge difference between the purchase price and the appraisal valuation, it's a good indication that something is amiss—the stone's qualities are exaggerated, or the gem has color or clarity treatments, or the gem was made in a lab. All these conditions lower the value of a gem.

What to do, in that case? Take a closer look at all the documentation, including sales paperwork. If necessary, call the seller and ask for clarification and documentation.

On a damage claim, ALWAYS have the jewelry examined in a gem lab that has reasonable equipment for the job and is operated by a trained gemologist (GG, FGA+ or equivalent), preferably one who has additional insurance appraisal training, such as a Certified Insurance Appraiser™. The inspection can verify that the quality of the jewelry is as stated on the appraisal and lab report.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com